LESSONS IN LUXURY REAL ESTATE

Rich people will by hugely expensive houses even if they hate them, and 15 other things I learned…By Trevor Cole

(Originally published 2003)

I want to make $1 million a year. In my hand should be the keys to an expensive car that I can write off entirely. My waking hours should be spent with exciting, wealthy people who consider me an expert in my field, though I have no extensive formal education. My sock feet should slide across floors of Italian marble, and overhead should arc ceilings no living man or woman can touch. I want to sell luxury real estate in Toronto. Welcome to my education.

Lesson One: Find the right role models

I'm told the top 2% of luxury real estate agents in Toronto will each make upwards of a million dollars in commissions this year. Some, by June, already have. If I want to be the best, I have to emulate the best. That means focusing on the top agents at the two premier high-end brokerages in Toronto—Johnston & Daniel and Chestnut Park. The first is older, in the business of selling downtown homes to the carriage trade in Toronto since 1950, and as a division of Royal LePage since 1994. The second began in 1990, when a splinter group of ambitious J&D agents formed their own company. By one count, these two brokerages accounted for 35% of the 132 deals for homes priced at $2 million or more in Toronto last year.

At J&D, the top two agents are Carole Hall and Caroline Wight. Ever since J&D was started by two chaps named Robert and Eggerton, who dreamed up the idea of employing “elegant ladies” to sell homes to the moneyed classes, high-end real estate in Toronto has been the enclave of what one J&D agent I've met referred to unkindly as “menopausal women.” But this should not suggest a type. Carole and Caroline, both in the upper reaches of middle age, could not be more different. Carole, a former Air Canada purser, is a sturdy strawberry blonde with a gruff, direct attitude that suits her black pin-striped suit. Caroline—that's pronounced “Carolyne,” I am informed by J&D's division manager, Catherine Moore—is a pixyish woman with short-cropped, salt-and-pepper hair, expressive eyebrows and a manner of speaking that suggests an English kindergarten teacher reading nursery rhymes to easily startled children.

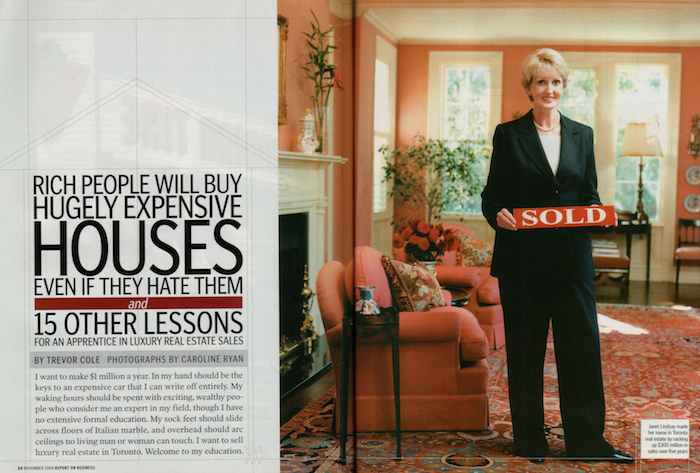

Over at Chestnut Park, I meet two more stars. The first is Janet Lindsay, a tall, austere (though strawberry blond) woman who's somewhat infamous for having recently taken the number-one status she established at J&D, (where she accounted for $300 million in sales over five years) and, along with several other agents, jumping ship to its main rival. The second is Jimmy Molloy, who was number one in dollar volume here until Janet arrived and who, though a man in his mid-40s, is nevertheless strawberry blond. Says a client of Jimmy: “He eats in the same restaurant as I do in Paris, so he must be rich.”

None of these agents will admit to making a million or more a year. That would be crazy. “They feel there is a lot of resentment toward the real estate industry as a whole,” explained one manager, as she tried to help me understand what a grave, grave event it would be to let this figure become public. “[An agent] does not want clients or anyone else to have that figure in their mind.”

Lesson two: specialize

If the Toronto real estate market is a truffle, each of my role-model agents sticks to the creamy, fattening centre—Rosedale, Forest Hill and thereabouts. Some have further areas of specialization. Janet Lindsay feels more comfortable in the Bridle Path than do many agents, who are perhaps unnerved by the influx of Chinese/Iranian/Russian money. Carole Hall handles more new homes than most, and focuses on Lawrence Park. “I live in Lawrence Park,” she says. “Your reputation in the area for selling is very important.” When I ask Carole if that means she would defer to a Rosedale-focused agent, such as Caroline Wight, if a potential listing came up there, she makes a face that assures me I am insane. “I have a large buyer right now for Rosedale,” Carole says, still making the face. “I'm not going to give that away to somebody else.”

Lesson three: establish a style

Janet Lindsay has her eyes on the deal. Well, at first she has her eyes on her new boss at Chestnut Park, CEO Catherine Deluce, because she's not sure what she's allowed to say. But once she gets comfortable, then her eyes are right there, on the deal. “I'm excited by the deal,” she says. “I love to negotiate, my adrenaline gets going and the challenge is terrific.” Janet also seems to be excited by success. Her website features a great big red “#1,” her business card commands me to “Work with a winner!!” and her e-mail address is “success@janetlindsay.com.” I have been told by someone back at J&D that Janet was “not a team player” there. And maybe that's why, when I asked Catherine Moore about the recent exodus of sales agents, she sniffed, “The people who left, we don't miss them.” But since Janet and the other agents came to Chestnut Park, its high-end market share has jumped substantially. By one estimate, of the properties sold in Toronto for $2 million or more in the first nine months of this year, Chestnut Park, with 110 agents, had a piece of 43%. J&D, with 150 agents, had 8%. So maybe the success-focused style is worth considering.

Jimmy Molloy, in contrast, is eager and friendly. “I don't perceive myself as a superstar real estate agent,” he says. “When people are finished dealing with me, they feel good about the process. I'm trying to make them feel like they're the star, their house is the star. This is what matters.”

To make his clients feel star-like, Jimmy strives to be helpful in unusual ways. Once, a client of his with a big house to sell came back from Tibet, or maybe it was Thailand, and he had burst blood vessels in his eye. Jimmy figured he should get that looked at, so he hooked him up with an eye surgeon client of his who happened to be looking for a house. So they met at the house, these two clients and Jimmy, and had a bottle of wine, and the buyer client checked out the vendor client's eye, and also looked at the house. Which he liked, except he preferred another area. But anyway, that's not the point. “The whole point is,” says Jimmy, “this guy's a client of mine. I just don't sell him real estate—I got him an eye exam.”

Lesson four: learn how to speak money

Agents of luxury homes don't refer to millions of dollars. A house does not cost “three million, six hundred and ninety-five thousand dollars.” It costs three six nine five. That house is two four six nine. This house is twelve seven five five. Avoid saying “million.” Don't ever say “dollars.”

Lesson five: get nice, respectable wheels

Jimmy Molloy drives a green all-wheel-drive Jaguar sedan. Carole Hall drives a white Jaguar sedan. Janet Lindsay drives a sleek black Cadillac sedan. Elise Kalles, the number-one agent and wife of Harvey Kalles, whose brokerage does most of its business in Forest Hill, travels from listing to listing in a chauffeured luxury car. You have to look like you could be driving to the very same party as your client.

Lesson six: houses aren't for touching

House showings are very good ways for agents to become familiar with properties. Between 11 a.m. and 1 p.m., most successful agents are either showing a house to other agents or viewing it. If you want to be sure agents see your house, you should offer sandwiches. The more expensive the house, the better the sandwich (smoked salmon for houses over $2 million is a good rule.) Because agents are polite and know that you want to keep the floors clean, they will take off their shoes. It is a very good showing if you have 50 agents walking around your house in bare feet with pink-painted toenails, eating your sandwiches.

Sometimes, however, because these are very nice properties, agents will become so enthusiastic about a house, they will want to touch it. This can be dangerous. Watch out for these warning signals:

“Oops. Uh, let's get out of here”—This means an agent has turned on a waterfall tap in the bathroom sink and had water splash all over the clean marble floor.

“Oh, shit!”—This means an agent has flicked a switch to watch the living room's eight-foot projection movie screen descend, only to see it jam up and crumple at one end.

Lesson seven: have connections to rich people

“Every person you deal with,” says an agent, “every contact, you hope to make them into a client.” Essentially, this means not spending a lot of your time with the unwealthy. One of the reasons Janet Lindsay belongs to theatre and charity boards is so that she can keep her ear out for who's coming to town and who's leaving. Not that she would ever cold call someone on the basis of a tip. “That,” says Catherine Deluce, “would not be appropriate.” It's more a matter of maintaining a presence, making yourself available to a potential client's whim. Jimmy Molloy, who once owned Auberge Gavroche, a Yorkville restaurant catering to a wealthy clientele (where he started as a busboy at age 15), keeps himself whim-ready through constant entertaining. “You should always use everything you're good at to your advantage,” says Jimmy. “Some people golf for business. I eat for business.”

And remember, there's all kinds of rich. Carole Hall got her first experience of the high-end life as an Air Canada purser. “When I did it, it was a very high-end job,” she says. “It introduces you to the taste.” Now a lot of her clients are athletes—the kind that fly first class. “The hockey players have made a big dent in our market. I've sold a lot of product to them.” Maple Leafs past and present number among her clients. She's got Darcy Tucker and Shane Corson in nice product right now. “They're two guys who actually listen.” Hockey players and their wives have traditional tastes—they like a nice French Country mansion. Driving through Lawrence Park, she can point out Joe Nieuwendyk's stately stone abode, and ex-Leaf Trevor Kidd's (for sale, $2.65 million). Trade time, says Carole, is “a good time to be selling.” You can bet no one wants a short lockout more than Carole.

Lesson eight: understand that rich people are different

Financing is usually not a condition in the offers for luxury real estate, but other conditions may apply. Janet Lindsay handled a sale where the buyer had to agree to let the seller leave his wine cellar untouched so that its contents could be removed, gradually, over a three-year period. On another occasion, the buyer and seller of a midtown property did business together, and the buyer was loath to jeopardize this relationship. So he prepared an offer, leaving the price blank, and let the seller fill in the amount. “I thought that was very gentlemanly,” says Janet.

Very often, rich people will buy hugely expensive houses even if they hate them. Recently, Caroline Wight was lucky enough to get the listing for a famous contemporary house on Roxborough Drive, all white cubes and glass vistas, that cascaded down a Rosedale ravine. The brochure she created called the $7.25-million home “a rare modernist masterpiece by architect Phil Carver . . . a one-of-a-kind residence [that] would be impossible to duplicate under present zoning regulations.”

A few weeks ago, the purchaser tore the house down. He'd bought it simply for the footprint. Though bylaws prohibit new homes from being built so close to ravines, they do allow renovation. Apparently, building a brand new house on top of an existing footprint fits the criteria.

An astonishing number of multimillion-dollar homes sold in this city are being razed and replaced. At the corner of Forest Hill and Russell Hill roads, Jimmy Molloy points out the window of his Jag at stately mansion after stately mansion. “That's new. The next two, new construction. That's new construction. That's new construction.” There's so much of it going on in Rosedale, residents who want to protect the historic character of the neighbourhood are fighting back. “Look what I got today, from the South Rosedale Ratepayers' Association, to put a stop to this.” Jimmy shows me a notice sent to specific high-end agents, warning them that certain houses in south Rosedale have been classified off-limits for demolition. For agents like Jimmy, this is a problem. “Right now I'm in a desperate hunt. I have a client who wants to build a house with an interior courtyard.. . . I gotta find a 110-foot lot, which is really rare to find, might involve two houses, buy 'em both and tear 'em down. And in Rosedale, if you buy it, you might not be able to tear down the house.”

On Park Lane Circle, in the Bridle Path district, a few doors down from Conrad Black's enormous mansion, Janet Lindsay motions matter-of-factly toward Gordon Lightfoot's enormous mansion: “That's what everyone wants today.” In the Bridle Path, as elsewhere, it doesn't matter to buyers if a house is old and outdated, or shiny and new; some dumpsters are going to get filled up. Says Janet of her clients, “They want their own dream.”

This is the business of luxury builder Joe Brennan, responsible for the construction of Gerry Schwartz and Heather Reisman's $25-million dream on Cluny Drive, and many others. “In the Bridle Path,” he says, “the lots are 3 1/2 million dollars. And those people want eight or 10,000 feet minimum.” The mansion at 20 Park Lane Circle, across from Lightfoot's house, is said to be 42,000 square feet.

Lesson nine: learn to be patient

At any point in time, Carole Hall, like most agents, knows how many buyers are out there. “We keep files on them,” she says. Right now her file pile is about eight inches thick, which means roughly 20 to 30 buyers. But that's in the regular price ranges. Over $3 million, the number drops to a handful.

“It's hard for houses to sell at the upper end in Toronto,” Joe Brennan tells me. Joe also builds in places like Palm Beach, where, he says, “I can name 20 houses that sold for more than $30 million.”

In the face of local resistance to the exquisitely expensive, Toronto agencies beseech the worldly client through international affiliations—with Sotheby's International Realty, in the case of J&D, and LuxuryRealEstate.com, in the case of Chestnut Park. Even so, the clamour for luxury properties in Toronto can be muted, and the frantic bidding wars common around lower-priced properties, quite rare. (Although you can be sure, when they do occur, they leave a warm glow. Caroline Wight managed such an event just a few months ago in Lawrence Park. It was, remembers Caroline dreamily, “a well-fought battle.”)

Typically, however, high-end properties in Toronto can take months or years to sell. I wondered how vendors felt about that, so I asked one. We'll call him Sid. “I don't care,” said Sid. A bit of a speculator, Sid has owned property in several countries. At the moment, he's not getting big enough offers for his downtown Toronto property, so he's going to wait, and use it in between trips to Nepal and Bangkok and Paris. “I'm not that wealthy,” says Sid. “But I have ‘fuck you' money.”

At the high end of real estate, many owners can afford to abandon properties and sit on them indefinitely. Prevented from altering a magnificent old Park Road house by those inflexible Rosedale ratepayers, billionaire David Thomson allowed it to sit open to the elements and animals for years, perhaps hoping it would fall down. (It was eventually bought and restored.) In the Bridle Path today, there sits a house that has been deserted for a decade, with leaks in the ceiling and black mould on the walls.

But these stories do sometimes have happy endings. Janet shows me a property on Park Lane Circle, two acres of land marked by a lovely 35-year-old Georgian home with ivy branches as thick as your forearm snaking through the eaves. “This was on the market for 2 1/2 years,” she says. The delay probably had nothing to do with the fact that, 27 years ago, a gardener drowned in the pool. At 5,000 square feet, the house was simply too small, and the lot, 750 feet deep but at most 150 feet wide, too narrow for a new structure of Lightfootian expanse. The price was reduced 10 times until it reached about $3.3 million, 40% below the initial asking price. It was bought by a Bay Street portfolio manager who plans, incredible as it may seem, to live in the house, perhaps because he can't afford to build anything new. “I don't think I'm your typical buyer here,” he says, a little sheepishly. “I have nothing for the living room.”

Lesson 10: your means is an end

A couple of decades ago, Canada's Competition Bureau took a hard look at the commissions charged by real estate agents, and particularly at the fact that, although commissions were supposed to be negotiable, they seemed to be stuck at 6%. So when I ask what the standard rate of commission on a high-end house sale is these days, I am told repeatedly, and somewhat anxiously, there isn't one. “That would be price fixing,” says Jimmy Molloy, “and that's illegal.” However, the most, shall we say, common rate is 5%. And when it's split between two agents, that means 2.5% “an end.”

How much of that an agent gets to keep depends on her performance. “It's a sliding scale depending on the agent's productivity,” says J&D's Catherine Moore. At J&D, as well as at Chestnut Park, the scale slides all the way up to 90%. At some other brokerages, such as the Sutton Group, agents get 100%, but then pay a monthly fee for services and desk rental.

Lesson 11: zip it good

Among luxury real estate agents, discretion is the law. “It's like the bedrock,” says Jimmy.

“What people at that level want more than anything else is discretion and privacy,” says Janet. Hockey trades are sealed and players put their houses up before the news hits the papers. It becomes obvious a CEO is on his way out when the board's chosen replacement is in town scouting for property.

“You get into a lot of personal information that you cannot allow anyone else to know about,” says Carole Hall. “The best realtor is somebody who doesn't remember the details.”

Of course, since the federal government instituted privacy legislation in January that makes discretion around the affairs of clients a legal necessity, it has become harder for the very discreet real estate professional to position herself. So when Caroline Wight says that she is often hired “because I am discreet,” she is also talking about the ability to orchestrate quiet deals outside of the Multiple Listing Service. Agents call them “pocket listings.” An agent lets it be known that she has a $5-million buyer. A potential vendor is alerted. The house is shown, the deal is done, and no one ever knows.

Lesson 12: learn to take a lot of crap

Jimmy Molloy keeps his BlackBerry beside his bed, in case one of his international clients in some far-off time zone has to talk to him. He knows they don't mind waking him up. “They want an answer, and they think it's funny,” Jimmy shrugs. “But that's the kind of personality I have.” Some of his clients, holdovers from his restaurant days, like to remind Jimmy of his roots. One of them, who Jimmy considers “brilliant” at real estate, was sitting down with Jimmy over a deal. Jimmy started to offer him advice. The client looked at him and said, “You used to be my busboy. Shut up.”

But not to worry, says Jimmy, he's a good friend. And anyway, “I'm not really confrontational.”

Since most high-end clients are gracious and respectful, it can be difficult getting the experience necessary to deal with the occasional louts. Luckily, Jimmy invited me to a cocktail party at the home of a wealthy acquaintance whom Jimmy was banking on turning into a repeat client, once he decides to sell his spread on Cluny Drive. The prospect was perfectly mannered, and enjoyed showing off his collection of antique hip flasks, but one of his guests, a rather well-known restaurateur, happened to notice the cardigan I was wearing. He leaned in and took the fabric between his thumb and forefinger. “What is that?” he asked with a kind of horror. “Cotton?”

Lesson 13: brochures are everything

I ask Catherine Moore, the manager at J&D, what special services a high-end brokerage is able to provide for the vendor of a luxury home. Apparently, it all comes down to brochures. “I know every realtor says they do this,” says Catherine, “but we really do a beautiful job on them: They're colour, they're on high-quality stock, they're absolutely beautiful.”

Agents will spend $5,000 and more of their own money, per house, on brochures such as these. If the property is truly remarkable, they will fly in a special photographer. So, naturally, they are very proud of them. Caroline Wight spreads out a number of brochures printed on glossy card stock. “This is the quality of the brochures that you don't normally find the average real estate broker offers their clientele,” says Caroline, pronouncing the last word “clee-on-tell,” as befits her upbringing in British India and Burma. “It is fairly obvious that this isn't desk-top printing.”

Jimmy Molloy is equally confident: “I think I do the best brochure.” He is particularly pleased with a brochure he designed for an extremely expensive home in Forest Hill. He had lovely long, panoramic images of the interior taken and printed on pages that he had turned sideways. “Since then,” says Jimmy, “a lot of people in my office are copying my design.”

Lesson 14: if you pretend someone is living in a house, rich people will believe it

There is a good deal of make-believe at work in the selling of high-end real estate. The first floor of Johnston & Daniel's offices, for instance, features a number of elegantly furnished rooms with labels on them such as “Living Room,” “Dining Room” and “Library.” Nobody is doing any living, dining or reading here—these are “closing rooms.” Never would you want clients to come to the second floor, where the sales agents have their offices, because then they might hear things, like frantic hubbub from middle-aged women who can't find their office manager and don't know her cellphone number, even though they've been told a hundred times! And they might see things, like photocopies of commission cheques of $109,439 and $103,191 and $102,865, framed and hanging on an agent's office wall. Better to place clients in the “Dining Room” and offer them a glass of water.

But the make-believe goes far beyond that. In fact, it goes all the way to Phyllis Newman.

Phyllis is one of a very select group of women, four or five at most, who “stage” high-end properties in Toronto. Other designers will do “fluffing”—adding flowers and pieces of accent furniture to spruce up a vendor's home before it goes on the market, but stagers, such as Phyllis, who become queasy and faint at the word “fluffing,” do far more. They work with builders before a home is completed, selecting the tiles, the fixtures, the finishes. And once a home is ready to come on the market, they do no less than create the illusion of life.

I met Phyllis, a smiling, high-pitched woman, in the foyer of a stately home on Bayview Wood in Lawrence Park. It was one of Carole Hall's listings, a resale property that had been on the market at $2.2 million throughout the summer of 2003 without getting a single offer. Carole realized she needed help and called in Phyllis, who assessed the problem immediately. “Everything was immaculate, but they were Armenian,” says Phyllis. “They had beautiful rugs, but their furniture was ethnic.” Adding to the predicament was wood stained an inappropriate oak colour, and green marble counters in the kitchen, and cupboards covered in—what do you call it? says Phyllis, oh yes—laminate.

Carole gave the order to have everything renovated, the clients agreed, and Phyllis went to work. “Why I'm excited about this house,” says Phyllis, excitedly, “is that the owners allowed me to do anything I wanted, and they didn't spare any cost.” For instance, the backsplash in the kitchen came in at $39 a foot. “Not everybody, even in the higher price range, will allow me to do that.”

Once the renovation was complete, after several months, Phyllis moved to phase two—the illusion part. She sweeps her hands around a ground floor filled with burnished antiques, clubby prints on the walls, tea service on the dining room table, mirrors and rugs and expensive soaps in the bath. “Everything here is mine,” she says. “The chandeliers, the draperies, the curtain rods—everything that's not nailed down.” In all, somewhere upward of $350,000 worth of set dressing.

Phyllis scours the antique stores and flea markets for what she calls “props” every day. She has two warehouses filled with the stuff of tasteful, luxury living, enough to stage two houses at a time. And with moving trucks and a team of assistants, she can, in a week or two of intensive effort, turn a shell of a house into something that mirrors a buyer's most fervent reverie, complete with a standard Ralph Lauren-look guest bedroom with horse-riding trophies that never fails to impress, Yves Delorme linens ironed and turned down just so, a deck of cards set out on a table as if a game had been interrupted and, in the kitchen, a surprising number of large plastic apples.

Phyllis roams her creation with an eye for details. She observes a display niche in the wall overlooking the curved stairway with disdain. “If I had my way this would have just been eliminated. Who has statues?” (She has placed a topiary in the niche.) In the richly appointed master en suite, she squeals with delight. “This is where they had to spend all their money.” She has the satisfaction of working without concern that clients will appreciate her taste. “That's the easiest part,” she says, “because they always love it.” Although no matter how much clients might love what she has done, they can never truly enjoy it, since no one is actually allowed to live in a house Phyllis has staged.

“You can imagine,” says Carole Hall. “How do you live perfectly?”

It costs as much as $45,000 for a month of Newman's illusion. “It's expensive,” says Carole, “but it's worth it.” This house is proof, having already been snapped up for $2.65 million, after being relisted for only a week. A colleague of Phyllis's, another stager named Margi, explains why all this works on prospective buyers: “This is how they actually envision themselves living,” she says. “This is what their home is going to look like, in their brain.”

But, I have to ask, can't wealthy clients look at an empty house and imagine it filled with their own beautiful things? No, apparently. “Ninety-nine percent of people,” says the stager, “simply don't have any vision.”

Lesson 15: toronto is rich and cheap at the same time

The number of rich people in Toronto is a constant source of joy for luxury real estate agents. Jimmy, driving through Yorkville, almost gives off a heat when the subject comes up. “There's a huge pot of money out there,” he says.

Sid, the speculator, has a theory: Toronto's wealth is filtering down and multiplying. “It's not necessarily the money that people have made that is buying these things,” says Sid, “it's two or three generations of wealth. So one million becomes three becomes six.” Jimmy, at the wheel, drives and nods his head at the same time. “There's been the biggest transference of wealth from one generation to another generation, ever.”

On top of that, says Janet Lindsay, thanks to the faster pace of today's economy, professionals don't have to wait 10 or 12 years to make their fortune, the way they used to. Take the financial industry. “That's a younger group,” says Janet, “making great amounts of money at a younger age than, say, my age group did.”

On top of that, you've got foreign rich people looking for a safe place to live. Parisians, Londoners, ready to drop seven million euros on the right place, and they come here and can't find anything priced to match. “We look so cheap to the Europeans,” says Sid, like he's embarrassed. And don't forget the Chinese from Hong Kong: They have a whole different idea of expensive.

“You've got all this money,” says Jimmy, more than a little excited, “and people are saying ‘what are we going to buy?'”

There is one major problem facing all this money: A client we'll call Art put it simply: “There is less great real estate in Toronto than there is in other major centres.”

He's much more polite about it than Sid. “Everything in Toronto is shit,” says Sid. “Toronto doesn't have one first-class apartment building. There's nothing with a 12-foot ceiling.” Sid prefers Paris, where ceilings are a proper 13 to 15 feet. Even Istanbul is better than Toronto, according to Sid.

If you're a new luxury real estate agent, like me, you listen to this sort of thing and you get to thinking—there's lots of wealth out there, but not much great real estate. That's a supply-demand scenario just ready to blow. Jack those prices up!

But not so fast.

Lesson 16: learn how high is too high

You talk prices with a real estate agent, and you're getting into touchy territory. Ask Janet Lindsay if a property listed by another agent is priced too high, and she'll say, “Now you're asking a political question.”

To secure their clients, agents are forced to do “beauty contests,” presentations in which they lay out their unique selling attributes and propose a marketing strategy. The crucial point here is always the suggested listing price, because it reflects not only the quality of the house, but also the agent's methodology and skill as a realtor.

Occasionally, an agent will pump up the suggested listing price, hoping to appeal to the client's greed, or at least his inflated sense of his property's value, knowing that eventually the price may have to be reduced. Sid has had an experience like this. “[A well-known agent] cost me a million bucks by overpricing my house, and then the market dropped.” Which is probably why, when you get Sid started on the topic of certain well-known real estate agents, it's hard to get him to stop. “They make me throw up! They have no idea what location is, what value is, what anything is. They just sell their connections.”

Most agents, if they're smart, will suggest a lower, more realistic price, promising a quicker sale. The fact is, an overpriced listing is nothing more than an expense. You'll be stuck pumping out brochures and sticking ads in the Globe at $150 a pop for months. Jimmy Molloy remembers a house on Boswell that came on the market roughly two years ago at $6.5 million. “I thought that I should have had the listing 'cause it was my neighbourhood,” grumbles Jimmy. “I do a lot of work in Yorkville.” Of course, that's a whole other issue, really. The point is, “I thought six five was a silly price. And it didn't sell for six five. I got it for three and I sold it in a month.”

Jimmy plays the “let's-be-realistic” card better than most. “Houses, overwhelmingly, sell for what they're worth,” he says. “It's an irrational market in that a lot of it is based on emotion, but inevitably market value always wins out. So if a house is priced at 10 and it's only worth seven, it's gonna sell for seven. It's just going to take a long time to get there.”

On the other hand, there are times when an opportunity is so good, you've gotta be a little gutsy. Be willing to stretch the envelope a bit. Jimmy's good at that too.

Driving through Forest Hill, he suddenly spins the wheel of his Jag: “I'll show you what I consider centre ice.” We turn off Lonsdale onto Dunvegan Road. From here to Kilbarry, he says, is one of the best real estate stretches in Canada. Half a block to the west is Bishop Strachan School for girls; half a block to the east, Upper Canada College for boys. He slows the car and points out one grand pile after another. There's a Tanenbaum. That's Ted Rogers. Down the street is Galen Weston. Honest Ed himself is there, David Mirvish is across the street. “Why,” exclaims Jimmy, “would you not want to live here?”

It was on this block, just a few years ago, that Jimmy sealed his reputation as a realtor with a gift. He had a beautiful property to work with, an exquisite building on 125 feet of gorgeously landscaped Dunvegan frontage. He analyzed the land value, the cost of construction, the intrinsic value of the landscaping and design, and the time spent arguing with contractors to get it just right (“That's worth a million bucks, easy,” he figured). He tried to find other properties to compare it with, and couldn't find a one; not even those priced at the top end, up there in the fives, could touch this property. And then he tied all those factors together, and set a listing price that no one had ever seen in Toronto before. Seven five.

Seven five.

And he got it. Other agents congratulated him for raising the bar. “Everyone said, ‘Molloy, you're a genius.'” But today he shrugs and thinks, well, maybe that's overstating things a bit. “I made the deal happen, I made it work,” he says. “But it was the property.”

As it happens, right on this block, at 135 Dunvegan, is the latest property to hit the high mark in Toronto. If you're interested in a 16,000-square-foot mansion on a double lot that once belonged to George Eaton, you're looking at $25 million.

Now, most agents will not openly admit what they think of this price. But you can pretty much tell from the way they roll their eyes. The vendor, a newspaper owner based in Hong Kong, won't disclose his original purchase price, but an agent recalls that the owner paid “four something” about 10 years ago.

However, when I suggested to the listing agent, Ilenna Tai of the Sutton Group, that most agents find her $25-million listing greatly inflated, she didn't seem at all troubled. “They just don't realize the potential of Toronto properties,” she said airily.

She's done her comparisons. She's looked at what it would cost to buy two adjacent lots in the prime section of Toronto; she's had architects from California assess what it would cost to knock down the mansions already on them and replace them with the structure being offered: 21,000 feet of living space (including the 5,000-square-foot basement), eight bedrooms, 13 washrooms, two libraries, a ballroom, a six-car subterranean garage with two car lifts, separate cellars for red and white wine, and an untold number of eccentric touches installed by the owner, including samples of his own poetry carved into the granite rocks in the garden, peculiar etched signs in the visitor's parking spaces (including “For fools and poets” and “For Rolls Royces only”) and a log cabin complete with a sign declaring it a museum marking the birth place of the fictional Rupert Dunvegan, who the owner dreamed up as part of a story to tell at parties.

She's also factored in the willingness of foreign buyers—particularly those from Hong Kong—to pay for the unusual degree of safety and serenity Toronto offers in a downtown setting, and the fact that there are many estates this expensive and more, out there in the King Cities and Caledons around Toronto, that may never come on the market. “If you look at that,” she says, “it's about priced in the right range.”

Besides, she says, the agents who make snide comments about the property's price are still happy to bring clients willing to submit their bank records for a chance to view it.

OTHER THINGS I HAVE LEARNED

-- No matter how beautiful they are, houses with one-car garages have a hard time selling. “At this level they've all got a Porsche stuffed away someplace,” says Carole Hall. And bubble-jet tubs are a must. “Nobody does Jacuzzi anymore.”

-- Architects cannot design houses that sell: “The architect draws the plans, he faxes the plans to me, I cut them to shreds,” says Carole. “When I cut them to shreds, then I give them to the builder and the builder cuts them to shreds.” They don't have enough closet space in the master bedroom, the bathrooms are too big, the washing machine and dryer are on the second floor. What—do they think the owner is going to do the laundry?

-- If a house is priced as though it's in a desirable neighbourhood, but it's actually one or two streets off, you need an out-of-town buyer.

-- Three good streets in Lawrence Park: Stratford, Stratheden and Glenallan.

Four prime Bridle Path streets: Post Road, High Point, Bridle Path and Park Lane Circle.

A good entry-level luxury street downtown: MacPherson Ave.

“It's a street that has great turnover,” says Jimmy Molloy.

-- Lawrence Park, with its British background, prefers traditional designs like Georgian and stone-heavy French Country. York Mills and Bayview buyers “want a splashier look,” Carole says. Properties on the North York side of Lawrence Park are more valuable, because there, you're allowed to build an approximately 4,200-square-foot footprint. On the Toronto side, it's only 3,000.

-- An oily rag placed over the sensor will keep Chestnut Park's automated garage door from closing—Jimmy Molloy's trick for fast ins-and-outs.

-- July is a good month for executives being transferred in. They need to get established for the start of the school year.

-- Nix the romantic lighting. “When people are coming to look at a house, they want to see it,” says Jimmy. He remembers the vendor of a particularly beautiful house, who worked very hard to create an enticing mood with the lighting. When Jimmy arrived for a showing, he would flick all the switches to high. “He'd say, ‘You're a philistine,'” remembers Jimmy. “I almost broke the poor vendor's heart.”

-- -- -- -- Don't take cash. “Since 9/11,” says an agent, “you just can't do deals like that. Cash is no longer cash.” It seems the feds have become pretty strict about money laundering. Anything over $10,000 is reportable, and telling a client you're reporting it is illegal. Once, a wealthy client tried to give this agent a $30,000 wad for a deposit. The agent wouldn't touch it, and doesn't even like talking about it: “We never had this conversation.”

By Trevor Cole