RELUCTANT HEIR

David Thomson’s life thus turns on a deeply troubling question: how to become your own man when you lack control of your destinyBy Trevor Cole

(Originally published in Toronto Life, 2001)

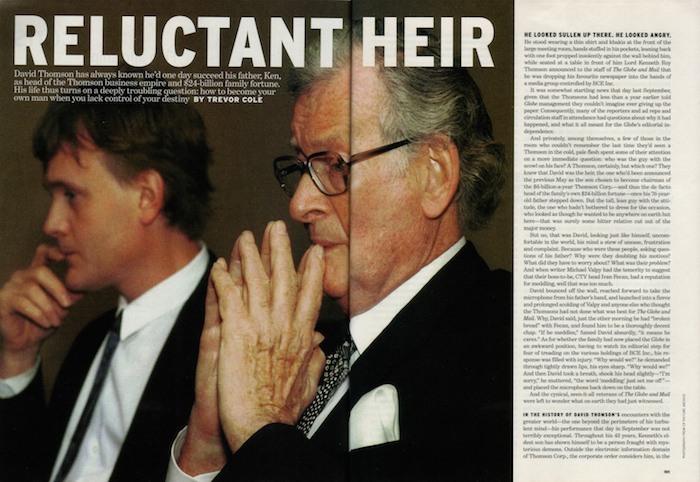

HE LOOKED SULLEN UP THERE. HE LOOKED ANGRY. He stood wearing a thin shirt and khakis at the front of the large meeting room, hands stuffed in his pockets, leaning back with one foot propped insolently against the wall behind him, while seated at a table in front of him Lord Kenneth Roy Thomson announced to the staff of The Globe and Mail that he was dropping his favourite newspaper into the hands of a media group controlled by BCE Inc.

It was somewhat startling news that day last September, given that the Thomsons had less than a year earlier told Globe management they couldn't imagine ever giving up the paper. Consequently, many of the reporters and ad reps and circulation staff in attendance had questions about why it had happened, and what it all meant for the Globe's editorial independence.

And privately, among themselves, a few of those in the room who couldn't remember the last time they'd seen a Thomson in the cold, pale flesh spent some of their attention on a more immediate question: who was the guy with the scowl on his face? A Thomson, certainly, but which one? They knew that David was the heir, the one who'd been announced the previous May as the son chosen to become chairman of the $6-billion-a-year Thomson Corp.--and thus the de facto head of the family's own $24-billion fortune--once his 76-year-old father stepped down. But the tall, lean guy with the attitude, the one who hadn't bothered to dress for the occasion, who looked as though he wanted to be anywhere on earth but here--that was surely some bitter relative cut out of the major money.

But no, that was David, looking just like himself, uncomfortable in the world, his mind a stew of unease, frustration and complaint. Because who were these people, asking questions of his father? Why were they doubting his motives? What did they have to worry about? What was their problem? And when writer Michael Valpy had the temerity to suggest that their boss-to-be, CTV head Ivan Fecan, had a reputation for meddling, well that was too much.

David bounced off the wall, reached forward to take the microphone from his father's hand, and launched into a fierce and prolonged scolding of Valpy and anyone else who thought the Thomsons had not done what was best for The Globe and Mail. Why, David said, just the other morning he had "broken bread" with Fecan, and found him to be a thoroughly decent chap. "If he meddles," fumed David absurdly, "it means he cares." As for whether the family had now placed the Globe in an awkward position, having to watch its editorial step for fear of treading on the various holdings of BCE Inc., his response was filled with injury. "Why would we?" he demanded through tightly drawn lips, his eyes sharp. "Why would we?" And then David took a breath, shook his head slightly--"I'm sorry," he muttered, "the word 'meddling' just set me off"--and placed the microphone back down on the table.

And the cynical, seen-it-all veterans of The Globe and Mail were left to wonder what on earth they had just witnessed.

IN 1984, DAVID PAID $14.6 MILLION FOR TURNER'S SEASCAPE, FOLKESTONE AND WATCHED IT QUICKLY TRIPLE IN VALUE

IN THE HISTORY OF DAVID THOMSON'S encounters with the greater world--the one beyond the perimeters of his turbulent mind--his performance that day in September was not terribly exceptional. Throughout his 43 years, Kenneth's eldest son has shown himself to be a person fraught with mysterious demons. Outside the electronic information domain of Thomson Corp., the corporate order considers him, in the words of one high-ranking Bay Streeter, to be somewhat "difficult" and "off the wall." His friends refer to the "intensity" that sets him apart. "It may be the case that David strikes some of his colleagues in the business world, who don't know that much about him, as an unusual or odd or slightly eccentric person," says his good friend Wesley Wark, a University of Toronto history professor specializing in espionage. But Wark prefers to imagine that "many people kind of relish the originality of him."

Eccentricity, as we know, is nothing new in a Thomson. David's grandfather, Roy, who grew the original Thomson fortune from the most meagre seed--selling auto parts and radios from the trunk of his car--was a man obsessed with wealth, who would dump jewellery and shiny trinkets from cloth bags and play with his glittering loot on the floor, who was once said to have told his wife, Edna: "For enough money, I'd live in hell." David's shy father, Kenneth, who oversaw the embellishment of the family riches, is famously parsimonious, notorious, in the description of Peter C. Newman, for delighting in a bargain on day-old buns and hoarding cookies away from household staff.

David's own affliction, however, is more poignant than comic, for his distinction seems to be an agonized intelligence caught between two lives--the one thrust upon him and the one he wants for himself--a mind trapped and gnawing on itself. Upon his father's death, he'll become the third Lord Thomson of Fleet, a prospect that darkens his mood. "It is something that has various connotations to it," he once said to an acquaintance, "and I would rather leave it behind." Last May, at the Thomson Corp. annual meeting held at Roy Thomson Hall, when Kenneth announced that his first son would be chairman within two years, David sat emotionless, wrote one reporter, "his pale eyes looking far away, his long thin face as still as stone." And later, reluctantly taking questions, he seemed bereft, unable to give an accounting of himself. "I feel my journey has yet to truly begin," he said. "I don't think I can adequately say there's an achievement that I'm proudest of." These were queer things to hear from the mouth of a rich man in his 40s. A Wall Street Journal writer, taking it all in, pronounced that "David didn't look quite ready."

And yet David has, in truth, been preparing himself for this for years, pushing himself, willing himself toward the reins he knew would one day be his. Elaborate trusts set up by Roy Thomson spelled out David's role before he'd reached adulthood. "David, my grandson, will have to take his part in the running of the Organisation," said Roy in his autobiography 26 years ago, "and David's son too.... These Thomson boys that come after Ken are not going to be able, even if they want to, to shrug off these responsibilities." Whatever unreadiness remains stands not as a testament to any lack of effort, but to the struggle David has had getting himself this far, and perhaps to lingering and tormenting doubts about the future unfolding before him.

IT WAS NEVER A GOOD BET THAT David Thomson would participate in this story. Roy may have been gregarious and even "revoltingly candid" in the view of the gentry he courted en route to his fortune and his peerage, but Ken has always shied like a woodmouse from public view, and David takes this habit to extremes. "The family controls about 200 newspapers and scores of other information concerns, and David," wrote a clearly frustrated Wall Street Journal staffer in 1989, "...has never been interviewed by any of them." He cultivates few friendships, conducts his transactions through numbered companies, and worries about exposure. There isn't even a visible street number on his grand white home on Rosedale's Roxborough Drive.

After David had refused once, through his secretary, I dropped off a letter at the nondescript front desk of Woodbridge, the Thomson family's holding company located on the 24th and 25th floors of 65 Queen Street West. It was a letter challenging him to slough off his shroud of secrecy and make the knowledge and ideas he'd acquired as a man of privilege more available to Canadians. Just a couple of hours later, David called. He'd found the letter "compelling," he said politely. It had "resonated" with him. But still, the answer was no. And two months later, when the publisher of The Globe and Mail, Phillip Crawley, suggested that David might now actually be willing to answer a set of written questions, I sent a sheaf of 57 of them, and never heard back. Perhaps the sheer number was overwhelming, or maybe it had simply been a sly means of determining what tack the article was going to take.

IT WAS AT UPPER CANADA COLLEGE THAT HE DEVELOPED HIS PROFOUND DISTRUST OF THE MOTIVES OF OTHERS. "I LEARNED THAT PEOPLE DID NOT GIVE A SHIT ABOUT ME, AND WHEN THEY DID, THEY WANTED SOMETHING. IT WAS AS BASIC AS THAT"

Still there's ample evidence of the kind of life David Thomson has led. There are the documents and footprints left behind whenever someone, no matter how wary, encounters the official world. There are the recollections and insights of his few close friends. And there was one instance when David encountered a journalist under exactly the right conditions, encountered him the way a man heavy-burdened with packages meets an onrushing cyclist, and let his troubles spill.

In 1993, while working on Old Boys, an oral history of Upper Canada College, James FitzGerald convinced David to sit down with him for an hour and a half. Thomson had loathed his experience at UCC, and took the opportunity to commiserate with a fellow alumnus. But David confided much more than his thoughts on UCC, and for the purposes of this article, FitzGerald graciously offered his transcript of David's testimony, most of which has never been published before.

FROM THE BEGINNING, DAVID THOMSON has found it hard being a Thomson. "He talks about that a lot, to selective people," says the gently spoken Wesley Wark, who in the echo of David's refusal becomes a kind of surrogate voice. "It's an inescapable burden."

By temperament, and then perhaps partly by necessity, he was an inward-looking child. His family's wealth and his own insecurities made him feel alone and isolated at UCC--"The prep was a traumatic time for me," he told FitzGerald--and so he sequestered himself, hiding in the washroom during recess, eschewing sports and avoiding the other children, who would sometimes rush up to the Fleetwood limousine he would arrive and leave in each day and try to hold the big double doors closed, until the chauffeur shooed them away.

It was here that he first developed his profound mistrust of the motives of others. "I learned at a very early age," he said, "that people did not give a shit about me, and when they did, they wanted something. It was as basic as that." He could easily have learned this from experience: one day, cycling with him along a bridge, a little boy said to David, "My mother is so happy that we are friends, because you are going to be able to do so much for me later in life." And David thought, "I wonder what it is that I am going to be doing for this chap?" But his suspicion of others also sounds like something his father has voiced. In contrast to dogs, who don't ask for much, wrote Vic Parsons in his biography of Ken, Thomson has observed that people "always want more."

A small child, one of those boys who was chosen last for teams and then picked on at every opportunity, he became haughty in self-defence. Even though, like his father before him and his brother to come, he was not an exceptional student--he once achieved a zero in math--he held himself above all but the most intellectual pursuits. Those he couldn't avoid--such as battalion, an exercise involving UCC cadets--he endured, just as he endured the rest of UCC.

What he did enjoy, more than anything else, was art class. He thought of it as a haven, a place where he could express his peculiar gift for aestheticizing his experience. When David was once caught talking and laughing in a class, he was banished to the hallway and made to suffer a classroom of children sent out to laugh at him. What he did was turn his back on them and look down the hall, where he saw the clock, and an office in the distance, and the natural light streaming past him, casting what he came to think of as "apparition shadows." He's held that image since he was seven years old.

When a three-year hiatus took him to the Hall School in England, which coincided with Roy Thomson's purchase of The Times of London and Ken's relocation to head the paper, David pushed himself to learn soccer. He hoped, he said, to "have people realize that the capability was of my own making, not something that was...an inheritance." Then he persevered through another five years at UCC--unlike his younger brother, Peter, who struggled and was sent to Royal St. George's College--and emerged with a shell prematurely hardened. "I lived, for so many years, feeling a sense of helplessness," he said. "Now I am extremely self-sufficient and rather overly aggressive, I suppose."

He was determined to shape his own reality, to be at no one's mercy. It wasn't a happy resolve; as he put it, "I would suffer, rightly or wrongly, from my own direction." But it became his central conflict: how to become his own man without having control over his own destiny.

And yet, his own direction looked oddly like one decided for him: he went to Cambridge University, just as his father had done. Although his marks never reached the first-class ranking that Ken achieved, it's fair to say that David found himself here. He buried himself in cerebral pursuits. "I have never been a rational sort of person," he said, "but intuition is the highest form of reason." Fancying himself a strategic thinker, he read history. And while he seemed to enjoy playing hockey with a loose group of Cambridge Canadians, dashing up the wing with vigour, he wasn't really someone you had fun with. "He seemed rather ascetic," recalls his friend Campbell Gordon, now chief operating officer of JP Morgan in Europe. "He wasn't the sort of person you'd think of going out and getting drunk with and ending up in some girlie bars or something."

He was, however, a man of persistent passions, art foremost among them. "If he wanted to learn about something," says Gordon, "he just disappeared until he'd mastered it." And though he could be brusque with people he felt were wasting his time, he had limitless patience for those, particularly older men, father figures, who had mastered the art of living in the world and were willing to share their secrets. One of these was a favourite London antiquities dealer, who mentored him in art collecting; another was his history tutor, who spurred David with questions like: What would you like to do? "Not a case of what you have to do," recalled David with awe. "What would you like to do?"

Throughout his time at Cambridge, still seeking an answer, David kept largely to himself, an observer. He developed his knowledge of art and his own talent for freestyle landscape sketching. "He was a very gentle personality, thoughtful, very curious," says David Camp, the son of Dalton Camp and now a Vancouver lawyer. The first time Thomson entered Camp's room at Queens' College, he noticed some Impressionist posters on the wall. "Oh," Camp recalls him saying, "you like this, do you?" and he went up to inspect them. And Camp remembers vividous," says David Camp, the son of Dalton Camp and now a Vancouver lawyer. The first time Thomson entered Camp's room at Queens' College, he noticed some Impressionist posters on the wall. "Oh," Camp recalls him saying, "you like this, do you?" and he went up to inspect them. And Camp remembers vividly once, after a hockey game, spending several hours with David in "the vault room" in the Thomsons' London home, quite astonished at the way he talked about and handled the pieces of art he had begun to acquire. "He cupped his hands so reverently," recalls Camp. "These things mattered to him. TheyThomsons' London home, quite astonished at the way he talked about and handled the pieces of art he had begun to acquire. "He cupped his hands so reverently," recalls Camp. "These things mattered to him. They were not just things he knew something about."

As a child, admiring some oil sketches owned by his father, David had become particularly fascinated with the work of John Constable, the English landscape artist who remains his enduring obsession. Those sketches, and one that David bought himself when he was 17, turned out to be the misattributed works of other artists. But at 19, having become friends with the 61-year-old Ian Fleming-Williams, a Constable expert, he acquired his first real one. So entranced was he by Constable's soft-focus elaborations of English country idylls that he and Wesley Wark took trips into the countryside surrounding Cambridge, where Constable had lived and painted. They would stop constantly on their various journeys, as David investigated museums and collections and dealers along the way, asking detailed questions about the finest works of this or that artist and where they could be found. "He is," admits Wark, "an exhaustive person to travel with."

And there was always the sense, among the few who knew him, that David was headed for a life more challenging than most of them could imagine. They saw the fresh stacks of the London Times that were hand-delivered to him. They knew that he spent many weekends with his grandfather, of whom he was in awe. They knew about the wealth created by spectacular investments in newspapers, in television, in oil.

But though he was headed for this life, his friends weren't sure he was entirely prepared. Wesley Wark thinks of him then, fondly, as someone living in his own insulated dream-scape. When David graduated from Cambridge in 1978, says Wark, "I think he thought it a more perfect, perfectible world than it really is."

And he seems to have thought himself a more perfectible man. A Trinity Hall tutor of David's, having observed him for a time, said to him, "You know, you are a cripple. You are something out of another world." And David thought to himself, "He is absolutely right. There are some very, very severe flaws here. Now, how did those flaws develop?" He burrowed into his own psyche, and began to develop a plan, a way by which he might chart his course through the real world. He thought, "In order to craft a direction or a pathway, these are the types of experiences that I will need. They will have to be humble experiences. I will have to draw the line. I will have to make a learning curve of probably 10 to 15 years, and at the end of it I do not want the money, the power or the position. I want the knowledge. They can never take away the knowledge."

BUT HE WAS STILL A THOMSON, and a believer in the Thomson cause. He bristled whenever a friend even mentioned the standard criticism: that the Thomsons had fuelled their fortune with newspapers penny-pinched into mediocrity. He loved his father and wanted to stand by him. His mother, Marilyn, pushed him firmly--harder than she did her two younger children--to bear the burden of the family fortune and name. And it was all much bigger than him. So rather than strike out on his own, rather than expose himself to a truly humble world, or even to the possibility of life as an artist--the way his brother Peter, now a photographer, eventually would, or his sister, Lynne, who later attempted an acting career in Hollywood--David assumed the family's ambitions as his own. He chose business, whether he was suited for it or not. He made it clear to his friend Wesley that he was doing so reluctantly. "He should have been an artist or an art collector, full stop," says Wark. "He knew that he was giving up a lot."

First he spent nearly a year at McLeod Young Weir, learning the investment banking business, and hating it. "It makes Upper Canada look like heaven," he said. And he was awkward around colleagues who wanted to socialize--when they invited him to go curling, the Cambridge man of art and history found it "eerie."

At the beginning of the 1980s, he entered the Thomson landscape. Having freshly acquired the Hudson's Bay Company at John Tory's suggestion in 1979, Ken decided that young David should learn about retailing. And David applied himself diligently in each department and post, becoming assistant to the general manager of one Toronto store, then manager of a store in Cloverdale Mall in 1983, progressing steadily along the path chosen for him.

But, of course, he wasn't the typical retailer. It wasn't just that he was the owner's son; he was...different. "He was always trying to find the hidden meaning behind things," sighs an HBC executive who worked with him. He was often critical of those who operated by rote without noodling around for a better way. And his art obsession tended to buoy tiresomely to the surface. It cropped up in conversations. He needed time off to visit auctions. There was a report of a meeting into which David brought a slide of a Constable painting, because it had occurred to him that if he could show his staff how every stroke was vital to the whole, he could demonstrate that every employee mattered.

By 1985, he sat at the elbow of George Kosich, then an executive VP of the Hudson's Bay Company and gunning for more. No doubt he saw Kosich as another of his teachers. David was an observer, but he didn't always see. "George Kosich, I think, used David Thomson for a while, to get George Kosich ahead," says the HBC exec. "Kosich sucked up to David. And David was a little naive at first."

They worked in tandem, first as executive and assistant. Then, in 1987, David was named to the HBC board and, roughly a week before his June 12 birthday, made president of Zellers ("I measure success by profits," he said dutifully). At the same time, Kosich happened to be winning a power struggle to become president of HBC. In July, some 250 of Zellers' head office staff were laid off. It was David's first month, but he declared it his own decision. Perhaps, having just been elected to the board of International Thomson Organization Ltd. (later merged with Thomson Newspapers into Thomson Corp.), he wanted to prove his worth. The HBC executive now says, definitively, "It was Kosich."

David ricocheted through the upper reaches of HBC like someone trying to get it over with. Six months after his Zellers appointment, he was president of Simpsons. By the beginning of 1989, he was chairman and CEO, though the appointment wasn't mentioned in the annual report's list of "notable developments." And by May 24, 1990, he was gone entirely, having moved his office from Simpsons into the Thomson building at Bay and Queen, where he began working more closely with Thomson's New York-based CEO, Michael Brown. He was becoming a vocal presence at every important board table in the Thomson group: HBC, Markborough Properties, Thomson Travel, Thomson Corp. itself. He was being steadily buffed and fed to become, a family confidant was quoted as saying, "custodian of the Thomson empire."

But there was a problem. Over on the publishing side, then the core of Thomson Corp., they didn't seem keen on listening to what David had to say. "I don't think the publishing department necessarily wanted him very much," says the HBC executive. "He went in there guns a-blazing, and a lot of people probably resented it over there."

In the higher reaches of Thomson Corp. and even Woodbridge, the family's own holding company, he was perceived by some as merely the heir. And it frustrated him. Hadn't he, by spending a decade in the world of investment banking and retailing, doing the merchandising and budgets and all the rest, proven himself a dedicated businessman? Didn't they realize what he could offer? David, says Wark, "always struggled with a sense that people didn't really appreciate his own independence, spirit, mind, or his own abilities."

And the fact that he had passions outside the world of business--did this make him less worthy? He had the sense that it did, and it made him peevish. "When you try to live a more balanced life, traditional businessmen think that you are not a real man," he grumbled. "But who is not the real man? You are telling me? You have not taken a weekend with your wife, you have no spare time that you use constructively, you do not have any hobbies, you do not know how to spell Mozart. And here you are telling me that I am weak? Let us just look. You are a human being that I pity, and I use the word pity very seldom. It is pathetic. You cannot get upset at these people. You just feel horrible."

AGAINST THIS AGGRAVATION, David tried to develop his personal world as a kind of balm. It wasn't a smooth process. He'd been wary around women, fearing the motives behind whatever interest they showed. He invited one woman up to his art-crammed room in his parents' home to see his collection--she noticed that he stood some of his paintings in the tub in an unused bathroom--but he never seemed to want things to...progress. "It was very odd," she says.

Eventually, though, David did find someone to love, and apparently trust. Her name was Mary Lou La Prairie, a beautiful young woman who had worked as a fashion buyer at Simpsons, and as the coordinator of a glossy ad supplement at the Globe. They were married in October 1988, amid white lilies and roses at Rosedale United Church. Together they had two children, Thyra Nicole and Tessa Lys, and appeared, for a time, happy. And David's friends, who felt protective of him, were pleased that he seemed to have found a secure and intimate family relationship.

He tried to create the perfect home. Yet here, too, he found frustration. In the mid-1980s, he'd bought the historic Geary house, on an enormous lot at 124 Park Road, and through 1986 and '87 his architects drew up plans and filed for permits to restore and improve the rambling old yellow-brick mansion. He wanted to alter the interior, remove the covered porch and build uncovered platforms, relocate the windows, change the dormers, demolish the coach house, even sever the lot to allow a second, more modern, home to be built. But it was all too drastic for delicate Rosedalean sensibilities, and his designs were continually thwarted by meddling neighbours in the ratepayers association. Protests were filed and letters sent to politicians while some basic structural and foundation work was done, but as the skirmishing continued, the workmen left and the house lay still and empty for more than a year, from April 1988 to May 1989. That was when the city revoked the building permits it had issued and considered the Toronto Historical Board's suggestion to expropriate the land.

It remained David's property, but he did nothing with it. For several more years, while he and his new wife made their home at another of his Rosedale properties, he left 124 Park Road derelict, its windows broken, its floors strewn with garbage and taken over by squatting animals, as if it were a monument to his refusal to let others dictate what he could or could not do, while neighbours and the city fretted about vagrants and the possibility of fire. He eventually put the property up for sale, in July 1992, for $3.2 million.

Sometime after that, serious fissures began to appear in the Thomsons' marriage, and on October 15, 1996--their eighth wedding anniversary--they officially separated. Just over a year later, citing "a complete breakdown of our marriage," and having weathered a "difficult and contentious" period up to and after the negotiation of their separation agreement, Mary Lou filed for divorce. She won shared custody of the children, a settlement of just over $6.3 million, an unspecified portion of property, and none of the art.

Today David devotes enormous energy to his children, loving them, says a friend, "beyond a normal parent." He takes them to sports events, skates with them, and picks them up midday from Branksome Hall so regularly that he's sure some of the mothers who see him assume he is out of work.

Ten days before he was announced at the Thomson annual meeting as the company's next chairman, David remarried, in his own immaculate white house on Roxborough Drive, the one with the glassed-in pool overlooking the trees of Moore Park Ravine that he seldom has time to draw. The bride was Laurie Ludwig, a public relations executive. It's a union some family members and friends are said to oppose.

ABOUT THE ONLY THINGS IT SEEMS David has been able to count on are his acquisitive passions. Failed by people, he has gathered around him things. In 1991, a partial published list included rare books from the Middle Ages, an original Charles Schulz cartoon, an animation cell from The Grinch Who Stole Christmas, remarkable sculptures and coins and, of course, the art--works by Edvard Munch, Piet Mondrian, Ivan Kluin, Cy Twombly, Mark Rothko, Picasso. J.M.W. Turner's Seascape, Folkestone, for which David paid $14.6 million in 1984, quickly tripled in value. And, of course, there was and is his ever expanding collection of paintings and drawings by John Constable, now arguably the world's greatest.

His other lust, less known but perhaps more important, is real estate. In the late '80s, chafing under the vexations of Thomson Corp., David looked for a way to prove himself a businessman on his own terms. And real estate, says Wark, "suddenly occurred to him." It had the advantage of being an area in which Thomson Corp. was not markedly skilled--its Markborough Properties, acquired through HBC, was on its way to being a billion dollars in debt. David, on the other hand, thought he might just have "a bit of a nose for it."

In 1989, he set up a real estate company called Osmington Inc.--undoubtedly named for a town on the Dorset coast where Constable and his wife spent a six-week honeymoon--by selling back to his father $95 million worth of Thomson Corp. stock (owned through his financial holding company Kluin). Since that moment of decision, he has steadily targeted ignored and undervalued office towers and built up an impressive collection of commercial properties. Most of these are owned through numbered companies, and the five employees at Osmington Inc., sticking to the Thomson privacy ethos, rebuff every inquiry. "We don't disclose anything about Osmington," says its CEO, George Schott. "Not for anybody." Last spring, Osmington purchased the Eaton Place mall and office tower in downtown Winnipeg. A few months later, it bought One Yonge Street, the Toronto Star headquarters, for almost $40 million. There are clues to other purchases. I was told by someone familiar with David's real estate movements that Osmington owns 335 Bay Street, the $6-million building where it keeps its head office, which is also where you find the head office of Emerald Property Services, another company linked to David. There are Emerald offices to be found in eight more commercial properties--six of them in Toronto, with an assessed value of almost $100 million. Four of those properties' owners list their mailing address as 335 Bay Street.

David's real estate ambitions led him to back Isiah Thomas's attempted takeover of the Raptors in the summer of 1997. Meeting the Thomson heir a couple of times, Thomas, now coach of the Indiana Pacers, had the impression that David was keeping himself at a distance. "He wasn't really into the details of the day-to-day negotiations," he says. But the idea of owning a sports franchise appealed to David enough that he later looked seriously at buying the entire Maple Leafs Sports and Entertainment Ltd. package, including the Raptors, the Leafs and the Air Canada Centre. "I remember him wondering," chuckles Wark, "where he was going to get the money."

Yet as happy as David seems to be stroking his real estate ambition, it remains, like his art collection, merely a hobby compared to the larger expectations of Thomson Corp.--and those he can't, or won't, escape. He seems intrigued enough by the world of newspapers and electronic information, and he does his homework, prowling through the offices of The Globe and Mail in his sneakers prior to the first BCE Globe Media board meeting in February. His fellow Thomson board members, at least the ones willing to speak, give him their full support. "I've never met a more focused individual once he puts his target in front of him," says Ronald Barbaro, chairman and CEO of the Ontario Lottery Corp.

Though he detests the arid and impassive culture of business, he seems resigned to it, as he was to UCC. "I still want to drive ahead and make a fortune and make things grow," he says. But even so, he is agonizing about that choice. Listen to the story he related to James FitzGerald, filled with an "I have this friend" air of confession:

"Recently, I went to lunch with a very prominent man who is my age," said David. "He was talking about an Upper Canada boy, and his father, who is extremely affluent. The father is a great financier. A marvellous man and great businessman, and his son is terribly gifted and creative. The father was pushing him very hard, into the financial end of the business.... But if the son is as talented as they say he is, he could make an enormously creative contribution by being allowed to pull up things from the deep, deep, deep abyss of his soul. He would probably shock his father and the whole organization. He would blossom, not only into a great businessman, but he would also be more at peace with himself. Because he would have been given a challenge within his own domain."

THERE IS ANOTHER PATH OPEN to David Thomson. Other men in his position, with similar interests and at the same point in their lives, have turned their backs on the relentless creation of wealth. John D. Rockefeller Jr., the art-loving son of America's first billionaire, filled with a sense of familial duty and once described as "always anxious and troubled," set business aside at the age of 36 and thereafter spent his time and fortune on philanthropy. Paul Mellon, the art-loving heir to the billions created by Andrew Mellon, did the same, and on his death in 1999 it took two pages in The New York Times to detail his contributions to society.

David Thomson could make that choice. It would represent a bold departure from the Thomson family's lengthy history of self-righteous parsimony, of guarding its columns of gold as jealously as it guards its privacy. He could, as the head of the Thomson fortune, make profound contributions to the cultural life of this city and this country. The yearly dividends alone--hundreds of millions of dollars--could save any number of threatened institutions. He could do all of that, make his mark, and be true to the better part of himself. But the other part of him is a Thomson, and in the face of suggestions that he or his father should give to a cause, he has always puled like a boy clutching a cookie. "There is always something that someone wants, and I have not figured out why."

Simply opening his art to the world would be a start. "I'd always thought that he should build an art collection for a broader public than himself," says Wark. "Partly because I thought he uniquely had the money to do that, partly because I thought he had the eye to do that." For most of his life, David couldn't imagine sharing his prizes. The idea of people coming to look at all he'd acquired, and having to answer their prying questions, dismayed him. But lately, that's begun to change.

In 1994 and '95, he allowed a portion of his Constable collection to be shown at galleries in New York, London and Toronto. He may have been instrumental in getting his father to loan some of his collected paintings and priceless miniature carvings to the Art Gallery of Ontario, which has led to discussions about a Frank Gehry-designed addition filled and partly funded by the Thomsons. And David has continuing conversations with Matthew Teitelbaum, director of the AGO, about other possibilities of which Teitelbaum refuses to speak. Wesley Wark has the sense that David has begun to see his collection as a public treasure, and is thinking now about how to use his wealth to contribute something positive. "You have to be in a bit of an independent position to be able to make those kinds of dreams come true," says Wark, "which I don't think he really was until fairly recently."

This is the beginning of David's way out, the chance to stop fretting about his predetermined path and establish his own way. But can he commit to it? "So many creative people compromise their true artistic talents at the expense of some larger expectation," David has brooded. "It can completely ruin your life." He speaks the words but sits, stone still, as the expectations close in. He seems willing to be trapped.

When Wesley Wark thinks of David, the picture in his mind is of someone immensely tired. "He lives an extraordinarily difficult life," says his friend. "The burdens of that life are very intense. And they're made doubly intense because he is a kind of imaginative, obsessive, detail-oriented artistic soul."

Under his final UCC class photo, in 1975, David wrote, "We are not so much victims of others as we are of ourselves." Yes, he admits, he was "a rather serious blighter" then. But he considered that fitting. "So many people rationalize and place situations and circumstances in other people's court," said David. "They are not honest with themselves. I have always been honest with myself. Because I am the only one who is. If I am not, I really am in trouble. No one else will tell me."

By Trevor Cole